Beyond LEED-Achieving True Sustainability

April 4, 2018

Ophelia Wilkins

When people in the building industry think of sustainability, they think of LEED. But LEED is first and foremost a rating system. It was developed to push the industry incrementally toward more environmentally friendly strategies. It doesn’t envision the ideal that we all need to be striving for. What would a truly sustainable building look like? And how would we know if we’ve created it? That’s where the Living Building Challenge comes in.

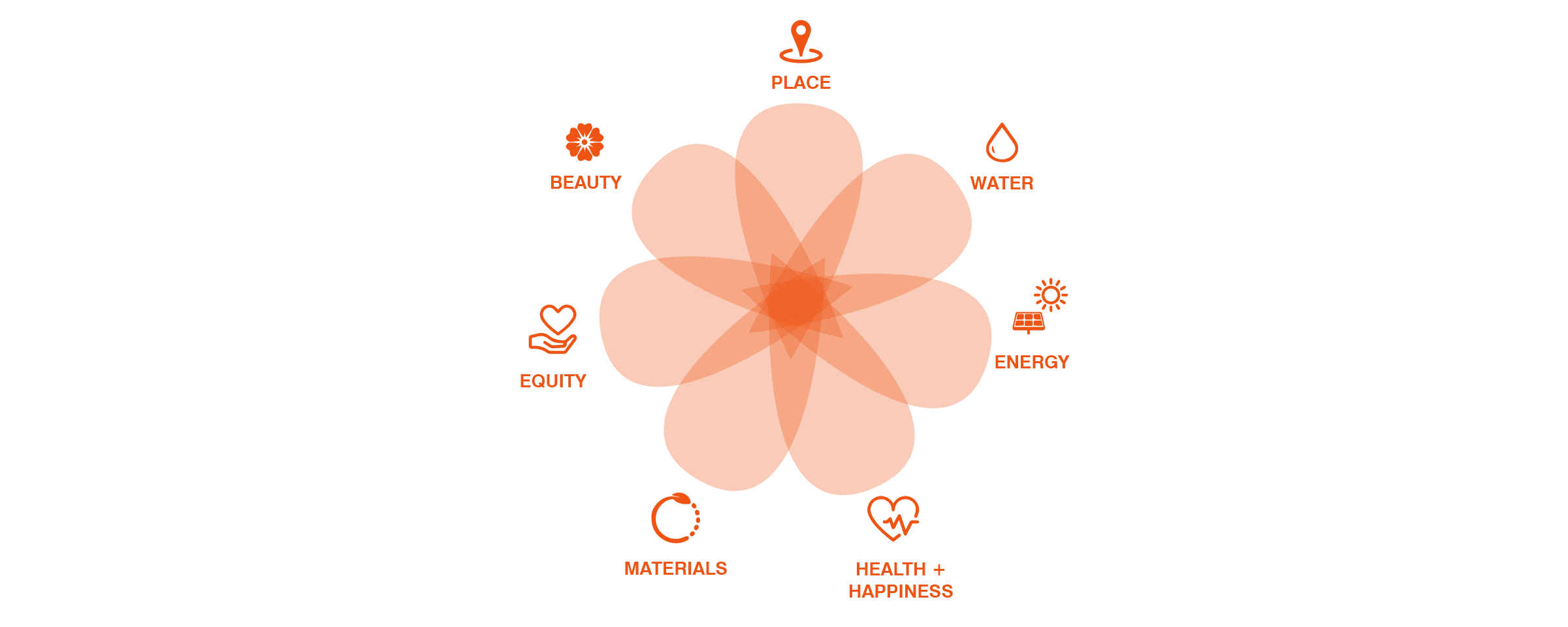

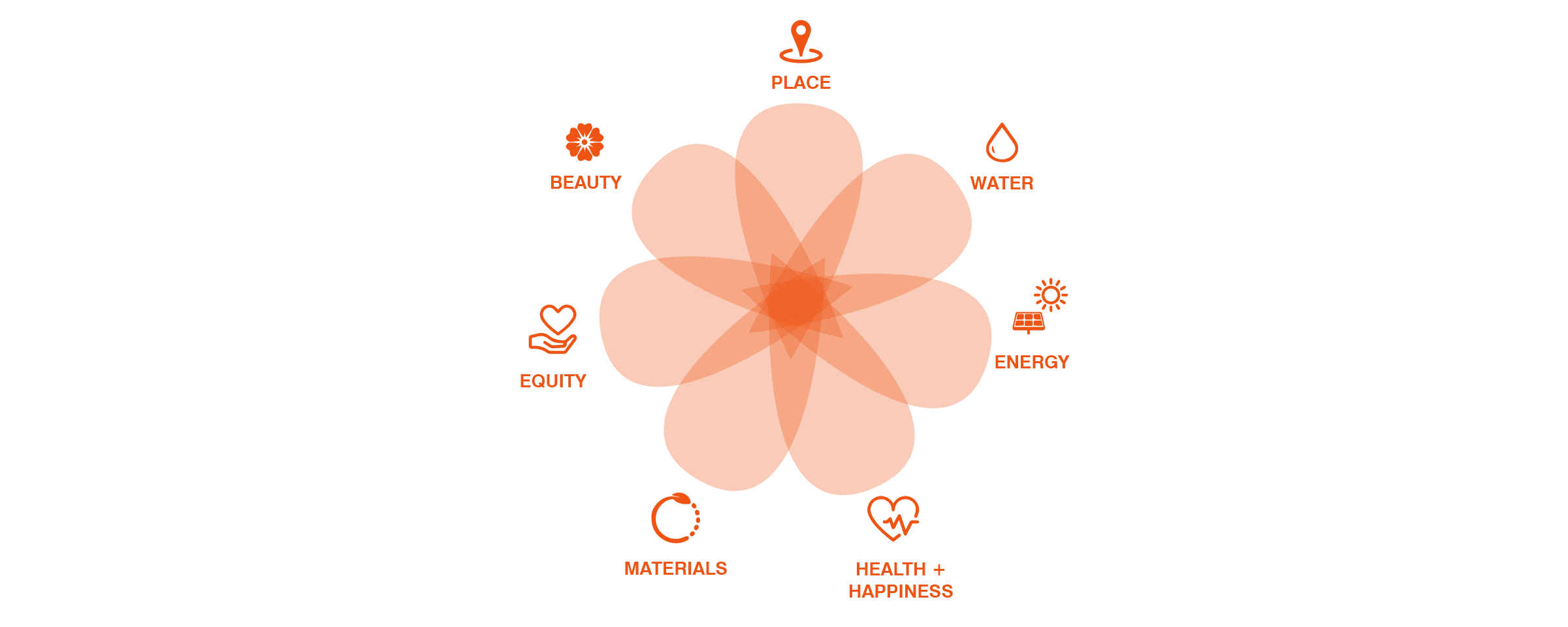

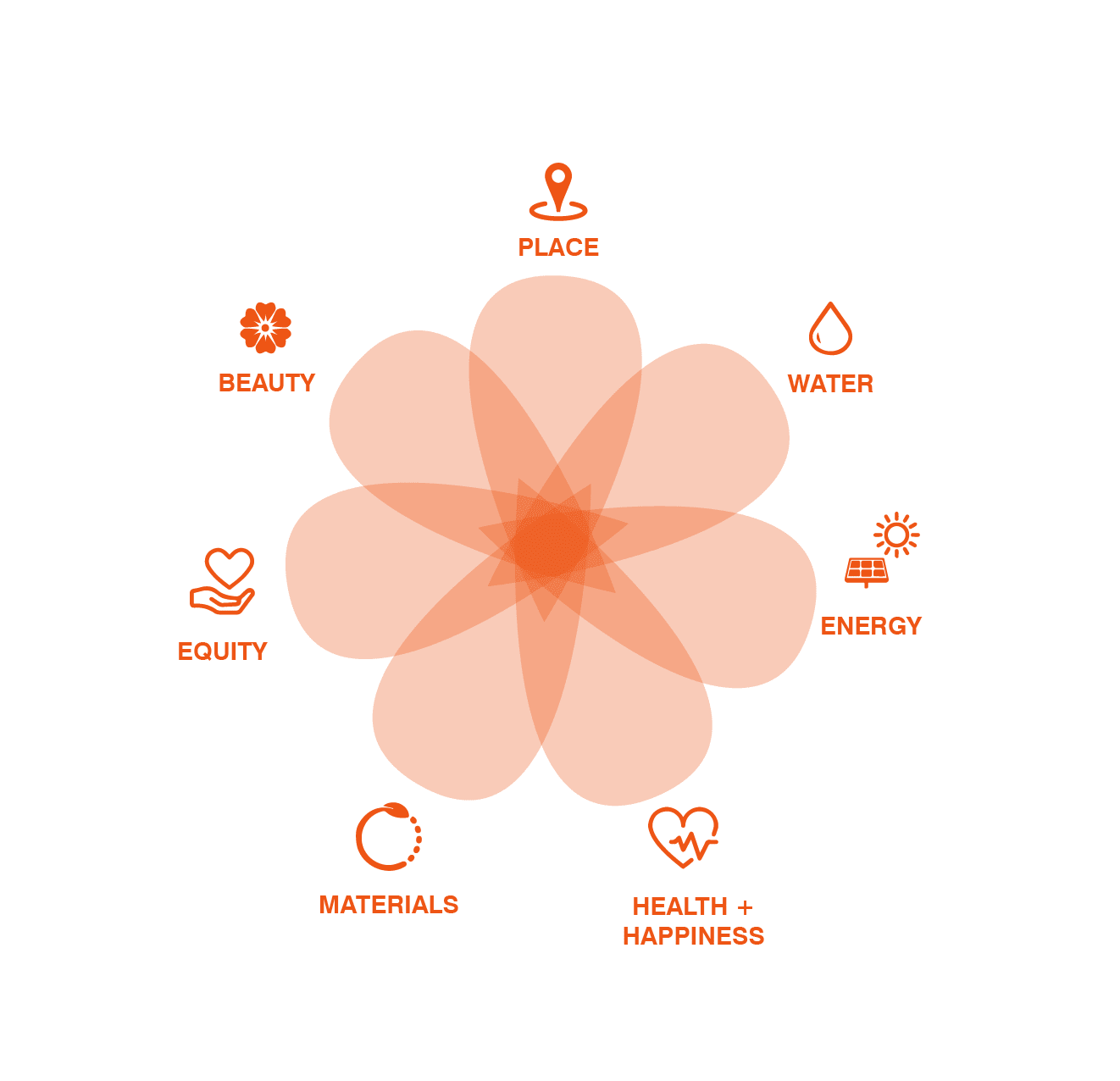

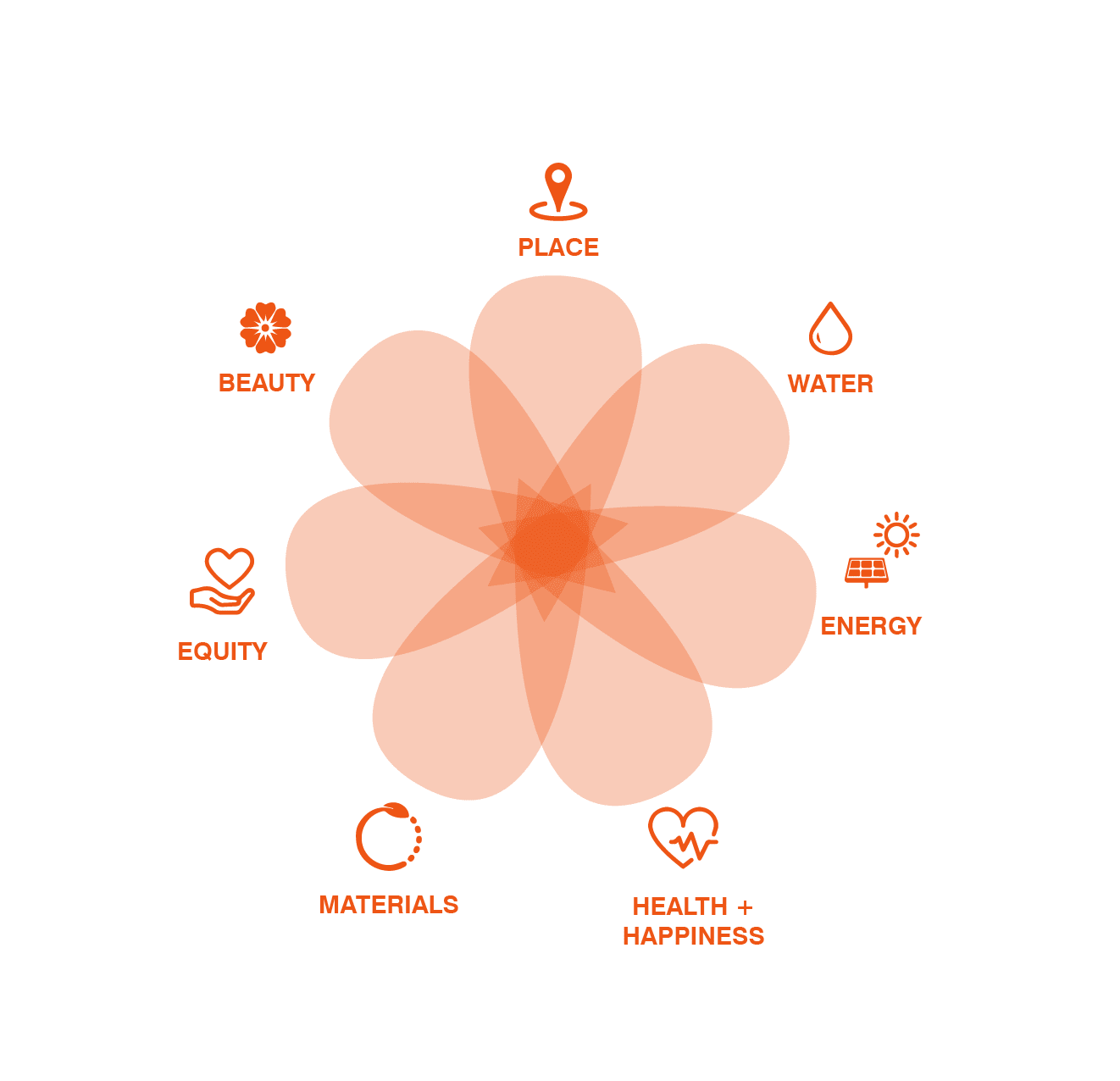

Think of the Living Building Challenge as a sustainable design framework and certification program for designers: it challenges design teams to be visionary, posing a complex problem in search of elegant solutions. Specifically, it asks us to “imagine a building designed and constructed to function as elegantly and efficiently as a flower: a building informed by its bioregion’s characteristics, that generates all of its own energy with renewable resources, captures and treats all of its water, and that operates efficiently and for maximum beauty.” The result? Buildings that contribute to the ecosystem around them as much as the natural landscape that originally occupied the site.

This certification program is comprised of seven performance categories, or “Petals”: Place, Water, Energy, Health & Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Beauty. A project that achieves three or more petals—one of which must be the Water, Energy, or Materials Petal—receives Petal Certification. Projects achieving all seven petals receive full Living Building Certification. Getting certification depends on actual performance. Projects must be operational for at least twelve consecutive months before being evaluated, to prove that that they have achieved their ambitions.

More than two dozen projects worldwide have received full certification since the program started in 2006, and nearly twice that number have received Petal certification. So it’s not just visionary—it’s doable.

The Bullit Center in Seattle, WA designed by Miller Hull Partnership is the first commercial office building to receive “Living” certification. It produces more power than it uses and collects its own water on site.

The Living Building Challenge is the creation of the International Living Future Institute (ILFI), an environmental NGO. In May, I went to the ILFI’s 11th annual Living Future unConference in Seattle. This was the sixth one I’ve attended. The content has evolved since I first started attending in 2009. Before the first Living Buildings were built and certified in 2010, content focused on the technical implementation of the Challenge, if it was even achievable. As Living Buildings have grown more plentiful and understood, the focus has shifted to gaining ground.

At the 2017 unConference, there was a lot of conversation about how to encourage more clients to go after the Living Building Challenge—not just get them to say, “Yes, this is what I want to do,” but to say it with conviction. The building owners who complete the certification process are the ones whose mission aligns completely with the goals of the Challenge. That’s why so many of the fully certified projects are for educational institutions or other nonprofits. Seeking a broader base of clients excited about going after the Challenge means finding new, and perhaps unexpected alignments between the owner’s goals and the challenge’s vision.

As the technology and methods for achieving Living Building Challenge goals become more widely known, the cost premium is decreasing and it’s becoming easier to evaluate the cost benefits. When an owner makes a commitment to the Challenge at the start of a project, the tools are now available to show their anticipated return-on-investment.

Social equity was another major theme at the 2017 unConference, rooted in the Challenge’s “Equity” performance category. As the technical imperatives have become increasingly understood, the Equity imperative has blossomed into a complex conversation about the relationship between the built environment and our social and cultural fabric.

Keynote speakers included Van Jones, CNN commentator and founder of Dream Corps under the Obama administration; Naomi Klein, author and activist; and Favianna Rodriguez, cultural strategist and the Living Future’s first artist-in-residence. All shared a background of social and environmental activism, none spoke directly of buildings. Collectively, they spoke to the practical skill of building greater understanding between people from different social and cultural backgrounds. They identified what brings people together: working towards shared goals, and tapping into human qualities that find resonance across cultures. Van Jones spoke to the imperative of creating a thriving environment for everyone. Favianna Rodriguez spoke about art as a vehicle for social change. Cultural acceptance of new ideas often happens once imagery makes its way into our daily lives.

Kuth Ranieri visits DPR’s San Francisco Headquarters, which received Net Zero Energy certification in 2015.

I’m hoping that Kuth Ranieri will have the chance to work on a Living Building Challenge project. After all, we have clients whose missions are highly aligned with the challenge’s goals. And I feel we’re highly prepared to do this kind of work. We’ve always had a strong environmental focus, and we love visionary thinking. These interests have been augmented by our collaborative work through DGDA, the Deep Green Design Alliance, (Kuth Ranieri’s green think-tank), which seeks cross-disciplinary solutions to environmental and civic challenges. Proposals such as Folding Water and Vertical Wetlands really gave us a chance to stretch our wings.

These projects, among others, exemplify visionary thinking paired with practical implementation that the Challenge articulates. Each intervention integrates within an existing or future ecology and proposes new forms of human interaction with our environment. Although un-built, they were developed through a collaborative design process informed by extensive research, making each proposal evocatively real. These projects were conceived before the Living Building Challenge became an established certification program, but they demonstrate that we have both the ethos and the tools to put ideas into practice.

Folding Water

Folding Water – Regional Plan

LEED created a consciousness in the industry and helped change the discussion. It’s played a strong role in raising the profile of sustainability. The Living Building Challenge has an essential and complementary role to play. It’s a call to visionary thinking, a reminder of the urgent purpose behind all this, and proof of the possibility of utterly transforming the relationship of the built environment to the natural world.

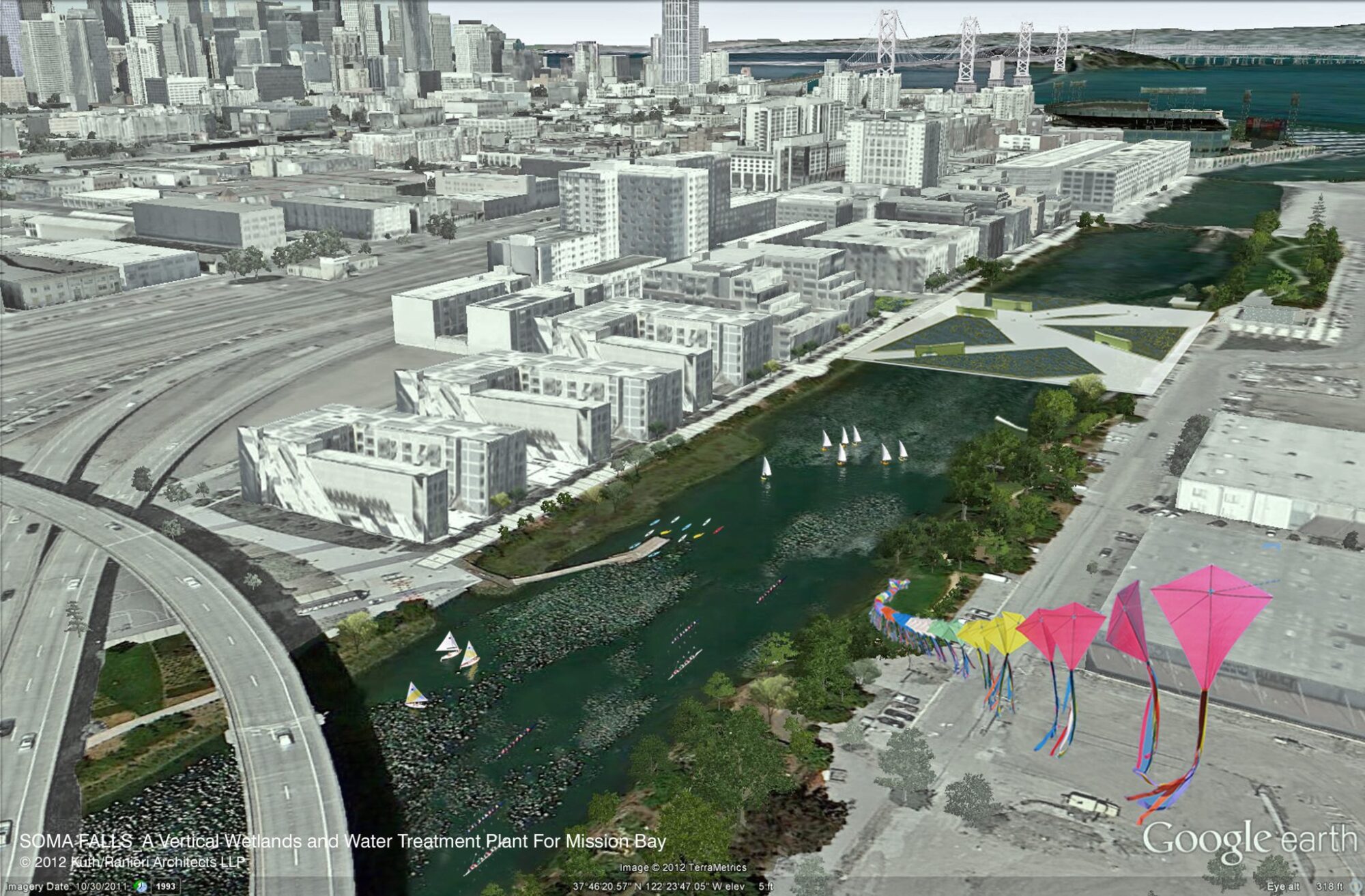

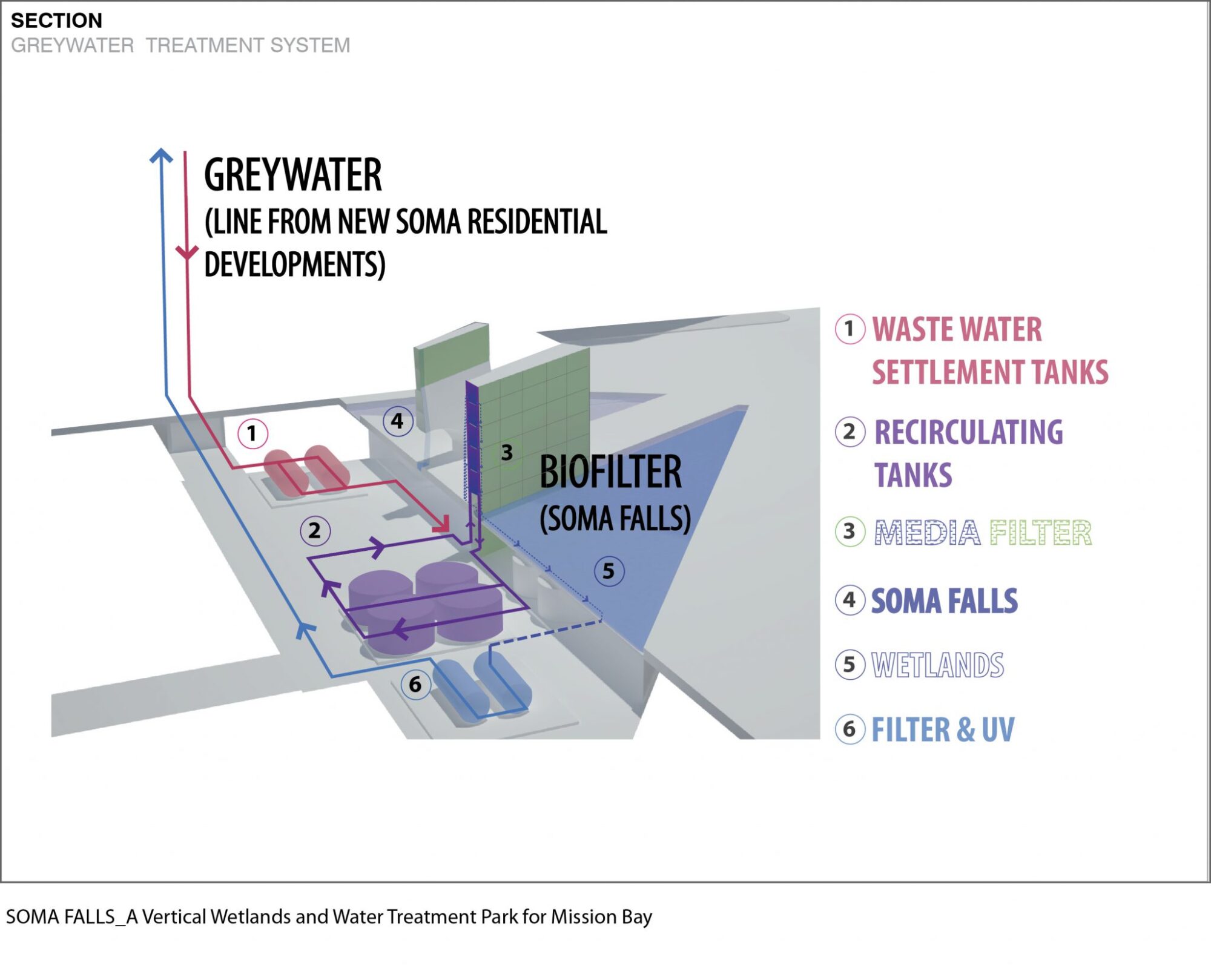

Vertical Wetlands

Vertical Wetlands – Plan

Vertical Wetlands – Greywater Treatment System Diagram

Beyond LEED-Achieving True Sustainability

Ophelia Wilkins

When people in the building industry think of sustainability, they think of LEED. But LEED is first and foremost a rating system. It was developed to push the industry incrementally toward more environmentally friendly strategies. It doesn’t envision the ideal that we all need to be striving for. What would a truly sustainable building look like? And how would we know if we’ve created it? That’s where the Living Building Challenge comes in.

Think of the Living Building Challenge as a sustainable design framework and certification program for designers: it challenges design teams to be visionary, posing a complex problem in search of elegant solutions. Specifically, it asks us to “imagine a building designed and constructed to function as elegantly and efficiently as a flower: a building informed by its bioregion’s characteristics, that generates all of its own energy with renewable resources, captures and treats all of its water, and that operates efficiently and for maximum beauty.” The result? Buildings that contribute to the ecosystem around them as much as the natural landscape that originally occupied the site.

This certification program is comprised of seven performance categories, or “Petals”: Place, Water, Energy, Health & Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Beauty. A project that achieves three or more petals—one of which must be the Water, Energy, or Materials Petal—receives Petal Certification. Projects achieving all seven petals receive full Living Building Certification. Getting certification depends on actual performance. Projects must be operational for at least twelve consecutive months before being evaluated, to prove that that they have achieved their ambitions.

More than two dozen projects worldwide have received full certification since the program started in 2006, and nearly twice that number have received Petal certification. So it’s not just visionary—it’s doable.

The Bullit Center in Seattle, WA designed by Miller Hull Partnership is the first commercial office building to receive “Living” certification. It produces more power than it uses and collects its own water on site.

The Living Building Challenge is the creation of the International Living Future Institute (ILFI), an environmental NGO. In May, I went to the ILFI’s 11th annual Living Future unConference in Seattle. This was the sixth one I’ve attended. The content has evolved since I first started attending in 2009. Before the first Living Buildings were built and certified in 2010, content focused on the technical implementation of the Challenge, if it was even achievable. As Living Buildings have grown more plentiful and understood, the focus has shifted to gaining ground.

At the 2017 unConference, there was a lot of conversation about how to encourage more clients to go after the Living Building Challenge—not just get them to say, “Yes, this is what I want to do,” but to say it with conviction. The building owners who complete the certification process are the ones whose mission aligns completely with the goals of the Challenge. That’s why so many of the fully certified projects are for educational institutions or other nonprofits. Seeking a broader base of clients excited about going after the Challenge means finding new, and perhaps unexpected alignments between the owner’s goals and the challenge’s vision.

As the technology and methods for achieving Living Building Challenge goals become more widely known, the cost premium is decreasing and it’s becoming easier to evaluate the cost benefits. When an owner makes a commitment to the Challenge at the start of a project, the tools are now available to show their anticipated return-on-investment.

Social equity was another major theme at the 2017 unConference, rooted in the Challenge’s “Equity” performance category. As the technical imperatives have become increasingly understood, the Equity imperative has blossomed into a complex conversation about the relationship between the built environment and our social and cultural fabric.

Keynote speakers included Van Jones, CNN commentator and founder of Dream Corps under the Obama administration; Naomi Klein, author and activist; and Favianna Rodriguez, cultural strategist and the Living Future’s first artist-in-residence. All shared a background of social and environmental activism, none spoke directly of buildings. Collectively, they spoke to the practical skill of building greater understanding between people from different social and cultural backgrounds. They identified what brings people together: working towards shared goals, and tapping into human qualities that find resonance across cultures. Van Jones spoke to the imperative of creating a thriving environment for everyone. Favianna Rodriguez spoke about art as a vehicle for social change. Cultural acceptance of new ideas often happens once imagery makes its way into our daily lives.

Kuth Ranieri visits DPR’s San Francisco Headquarters, which received Net Zero Energy certification in 2015.

I’m hoping that Kuth Ranieri will have the chance to work on a Living Building Challenge project. After all, we have clients whose missions are highly aligned with the challenge’s goals. And I feel we’re highly prepared to do this kind of work. We’ve always had a strong environmental focus, and we love visionary thinking. These interests have been augmented by our collaborative work through DGDA, the Deep Green Design Alliance, (Kuth Ranieri’s green think-tank), which seeks cross-disciplinary solutions to environmental and civic challenges. Proposals such as Folding Water and Vertical Wetlands really gave us a chance to stretch our wings.

These projects, among others, exemplify visionary thinking paired with practical implementation that the Challenge articulates. Each intervention integrates within an existing or future ecology and proposes new forms of human interaction with our environment. Although un-built, they were developed through a collaborative design process informed by extensive research, making each proposal evocatively real. These projects were conceived before the Living Building Challenge became an established certification program, but they demonstrate that we have both the ethos and the tools to put ideas into practice.

Folding Water

Folding Water – Regional Plan

LEED created a consciousness in the industry and helped change the discussion. It’s played a strong role in raising the profile of sustainability. The Living Building Challenge has an essential and complementary role to play. It’s a call to visionary thinking, a reminder of the urgent purpose behind all this, and proof of the possibility of utterly transforming the relationship of the built environment to the natural world.

Vertical Wetlands

Vertical Wetlands – Plan

Vertical Wetlands – Greywater Treatment System Diagram